In 1847, on the north shore of Zealand, as Danish citizens fought for “freedom of press, and religion,”1 fourteen-year old Hans Sorensen finished school and entered apprenticeship. That same year his mother and grandmother died. In 1849 the monarch gave in and the people won their desired freedoms.2 With a feeling of opportunity, Hans studied with a demanding shoemaker, and using local materials he became skilled at constructing shoes and saddles with maple pegs and strong flax thread.1 He was among the “industrious, peaceable, and skillful,”3 of his people. At age 20 his brother and father died4 but he continued his trade and service to his community. Nine years later, he married Maren Kristine Hansdatter also of his Parish and opened a shoe-shop in the nearby town of Tisvilde.1 The 1864 conflict with Prussia and Austria pulled him away from his work and bride as he was drafted in the 2nd battle of Schleswig-Holstein.1 He survived the painful war but Denmark lost significant portions of the country.2 Religious freedom was crossing the country as were the Mormon missionaries. As predicted by a Latter-day Saint leader, the war served to, “awaken the indifferent and the careless to a sense of their situation, and thus [brought] many into the Church…”3 Hans attended a Latter-day Saint meeting, “was impressed with their message… investigated…the doctrine, and was satisfied he had found the Pearl of Great Price.”1 #Ancestorclips

In 1847, on the north shore of Zealand, as Danish citizens fought for “freedom of press, and religion,”1 fourteen-year old Hans Sorensen finished school and entered apprenticeship. That same year his mother and grandmother died. In 1849 the monarch gave in and the people won their desired freedoms.2 With a feeling of opportunity, Hans studied with a demanding shoemaker, and using local materials he became skilled at constructing shoes and saddles with maple pegs and strong flax thread.1 He was among the “industrious, peaceable, and skillful,”3 of his people. At age 20 his brother and father died4 but he continued his trade and service to his community. Nine years later, he married Maren Kristine Hansdatter also of his Parish and opened a shoe-shop in the nearby town of Tisvilde.1 The 1864 conflict with Prussia and Austria pulled him away from his work and bride as he was drafted in the 2nd battle of Schleswig-Holstein.1 He survived the painful war but Denmark lost significant portions of the country.2 Religious freedom was crossing the country as were the Mormon missionaries. As predicted by a Latter-day Saint leader, the war served to, “awaken the indifferent and the careless to a sense of their situation, and thus [brought] many into the Church…”3 Hans attended a Latter-day Saint meeting, “was impressed with their message… investigated…the doctrine, and was satisfied he had found the Pearl of Great Price.”1 #Ancestorclips

(1) Sorensen, George H, Hans Sorensen, as compiled in Hardman Biographies, Ancestors of Sidney Glenn Hardman and Dorothy Mae Griffin, Dec. 2009

(2) Wikipedia.org

(3) Christensen, Marius A. History of the Danish Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day-Saints, A Thesis, BYU, March 1966

(4) FamilySearch.org (photo of Hans Sorensen, and other information)

(5) Painting from Vejby in Nordsjaelland by Johan Thomas Lundbye, 1843, commons.wikimedia.org

Author Note:

Hans Sorensen is my great-great grandfather. I sense from him a patient, day-by-day determined character who followed his heart even in the face of loss. In his youth, he lost his grand-parents, parents, and a brother. As a new groom, he was taken from his wife for war. As a seeker of truth, he lost his friends and extended family. Yet, the choices later in life demonstrate that he built upon the strong character of his youth. He followed his heart. He worked hard, built a family, and became a blessing to his posterity and his ancestry by his faithfulness to God. Truly he lived the commandment to ‘honor thy father and thy mother’ (Exodus 20:12) including ancestors by the life he lived. As one in his family tree, I can draw from the seeds of patient character and diligence inherited from Hans Sorensen.

Andrew Peterson was surely heartbroken when his sister Johanna was thrown from a buggy, her dress caught in the wheel, and dragged to death. A heckling mob had frightened the horse, persecutors of the Denmark Mormons. Instead of giving up, the spirit of truth urged Andrew on, he taught the Gospel for a number of years. Then in faith he accepted a mission call to his home country of Sweden where he met and taught widow Greta Pherson and her daughter Anna Maria. Like Andrew, Anna Maria felt the truth, embraced the covenant of baptism and joined Andrew and his family for immigration to America following his release. They travelled from Copenhagen to the major seaport Hamburg and boarded the ship Athena with the saints. Before heading to the North Sea on the river Elbe, the captain needed more room for passengers. He learned that there were six couples engaged to be married. Calling them together he told them he had the authority to marry them and if they would allow this he would have the cooks prepare wedding cakes for each couple and all they could hope for in a wedding dinner. This way he would have six extra beds. Each couple chose to marry including Andrew and Anna Maria. They travelled by sea, rail, and wagon finally settling in Lehi Utah, true to their faith and advocates for Scandinavian saints that would follow.

Andrew Peterson was surely heartbroken when his sister Johanna was thrown from a buggy, her dress caught in the wheel, and dragged to death. A heckling mob had frightened the horse, persecutors of the Denmark Mormons. Instead of giving up, the spirit of truth urged Andrew on, he taught the Gospel for a number of years. Then in faith he accepted a mission call to his home country of Sweden where he met and taught widow Greta Pherson and her daughter Anna Maria. Like Andrew, Anna Maria felt the truth, embraced the covenant of baptism and joined Andrew and his family for immigration to America following his release. They travelled from Copenhagen to the major seaport Hamburg and boarded the ship Athena with the saints. Before heading to the North Sea on the river Elbe, the captain needed more room for passengers. He learned that there were six couples engaged to be married. Calling them together he told them he had the authority to marry them and if they would allow this he would have the cooks prepare wedding cakes for each couple and all they could hope for in a wedding dinner. This way he would have six extra beds. Each couple chose to marry including Andrew and Anna Maria. They travelled by sea, rail, and wagon finally settling in Lehi Utah, true to their faith and advocates for Scandinavian saints that would follow. Nine-year-old Edna ran through the orchard with her straight brown hair flapping in the summer air. “Hey Myrtle!” She called back to her ten-year-old sister. “Watch this.” Edna jumped on to a pig, patted his side, and held on. “We’re supposed to be feeding them,” Myrtle pretended to object. “not riding them.” Myrtle looked back toward the house, then dropped her apple bag and with bouncing curls chased down another pig. Both girls laughed, squealed, and finally fell on the orchard grass, giggling, trying to keep their hair out of the rotting summer apples. ‘Emily Myrtle’ and ‘Edna’ Elton were the youngest of eight. The children were taught to be honest, to mind, and to respect and care for others. For chores they packed wood and coal, gathered grain, hauled hay, white-washed walls, pressed apples, thinned beets, and herded sheep. They found fun in many chores as they wove plant stems into chains, made up songs, played school, and ate lunch in the fields with dad. In the winter they rode sleigh, fashioned snowmen, and laid on their backs making snow fairies. Christmas gifts were few, but given with love, then cherished. On Sunday they had a bath in a number three metal tub and wore their treasured Summer dress to church. Forever young and beautiful on the outside, they were playful, loving, and devoted on the inside. Myrtle and Edna loved life, not wishing for things they didn’t have. Their simple dreams fed their imaginations and added spice to their lives and all who knew them.

Nine-year-old Edna ran through the orchard with her straight brown hair flapping in the summer air. “Hey Myrtle!” She called back to her ten-year-old sister. “Watch this.” Edna jumped on to a pig, patted his side, and held on. “We’re supposed to be feeding them,” Myrtle pretended to object. “not riding them.” Myrtle looked back toward the house, then dropped her apple bag and with bouncing curls chased down another pig. Both girls laughed, squealed, and finally fell on the orchard grass, giggling, trying to keep their hair out of the rotting summer apples. ‘Emily Myrtle’ and ‘Edna’ Elton were the youngest of eight. The children were taught to be honest, to mind, and to respect and care for others. For chores they packed wood and coal, gathered grain, hauled hay, white-washed walls, pressed apples, thinned beets, and herded sheep. They found fun in many chores as they wove plant stems into chains, made up songs, played school, and ate lunch in the fields with dad. In the winter they rode sleigh, fashioned snowmen, and laid on their backs making snow fairies. Christmas gifts were few, but given with love, then cherished. On Sunday they had a bath in a number three metal tub and wore their treasured Summer dress to church. Forever young and beautiful on the outside, they were playful, loving, and devoted on the inside. Myrtle and Edna loved life, not wishing for things they didn’t have. Their simple dreams fed their imaginations and added spice to their lives and all who knew them. On September 11, 1777, General Washington collided with the British here at Brandywine Creek, Pennsylvania; booming cannons echoed 25 miles east to Philadelphia. There were heavy American losses on the battlefield. John Coon Jr. was serving his apprenticeship nearby and heard the blasts, a penetrating sound for a 9 year old. ([1] Goble, pg. 120, ref 12). The very next spring, the British launched “a secret night assault [10 miles] to the north in Paoli.” Not yet aware of the attack, “John Coon roused himself from…his thick…German-feather comforter. He rubbed the sleep from his eyes and stretched to greet the dawn. Clad simply in a long nightshirt, he stepped…into his britches…, pausing only to splash water on his face and straighten his thick [untidy] hair… His thoughts were on his chores, [and] the few moments he could spend in his forested hideaway at Brandywine Creek catching fish for breakfast, and [then] his afternoon at the cooper shop…” (Goble, pg. 123) But, instead of a pleasant spring morning, the penetrating sounds of death again rolled like thick fog across the Great Valley. Word spread that 150 Colonials were found dead. As the wounded “were transported…along the road through Chester,” the neighborhood wept at the groans of the dying. As a young man John experienced these realities but continued industrious and of service to family and country in Pennsylvania, Virginia, Ohio, and Illinois. At age 16, after the death of his father, he returned home to Lancaster, “rented a barn, and freighted [for the local militia] until he married,” (Goble, pg. 124, 129) at age 30. He was becoming a “tower of strength and manhood” upon whom his present and future family could trust. (see Goble, pg. 130) Thank you, to those who served here, and thank you, to my 4th great-grandfather, John Andreas Coon Jr.

On September 11, 1777, General Washington collided with the British here at Brandywine Creek, Pennsylvania; booming cannons echoed 25 miles east to Philadelphia. There were heavy American losses on the battlefield. John Coon Jr. was serving his apprenticeship nearby and heard the blasts, a penetrating sound for a 9 year old. ([1] Goble, pg. 120, ref 12). The very next spring, the British launched “a secret night assault [10 miles] to the north in Paoli.” Not yet aware of the attack, “John Coon roused himself from…his thick…German-feather comforter. He rubbed the sleep from his eyes and stretched to greet the dawn. Clad simply in a long nightshirt, he stepped…into his britches…, pausing only to splash water on his face and straighten his thick [untidy] hair… His thoughts were on his chores, [and] the few moments he could spend in his forested hideaway at Brandywine Creek catching fish for breakfast, and [then] his afternoon at the cooper shop…” (Goble, pg. 123) But, instead of a pleasant spring morning, the penetrating sounds of death again rolled like thick fog across the Great Valley. Word spread that 150 Colonials were found dead. As the wounded “were transported…along the road through Chester,” the neighborhood wept at the groans of the dying. As a young man John experienced these realities but continued industrious and of service to family and country in Pennsylvania, Virginia, Ohio, and Illinois. At age 16, after the death of his father, he returned home to Lancaster, “rented a barn, and freighted [for the local militia] until he married,” (Goble, pg. 124, 129) at age 30. He was becoming a “tower of strength and manhood” upon whom his present and future family could trust. (see Goble, pg. 130) Thank you, to those who served here, and thank you, to my 4th great-grandfather, John Andreas Coon Jr. Anne Marie gasped as her knees buckled. She sat down immediately on the rough porch covering her mouth with one clinched hand, holding her chest with the other. She widened her beautiful gray eyes to prevent tears from falling, which eventually spilled to the ground. She had married in Denmark, leaving her “quaint Danish home…dirt floor and thatched roof,” and set sail with her new born child promising to work hard and send money so her husband could join them in America. Her mother and brother had immigrated earlier and by their toil had saved and sent enough for Anne Marie to come. “She crossed the North Sea,” where she and the child suffered terrible sea sickness. Now in Richfield, Utah, “she scrubbed floors and cleaned to…take care of her little son. When she had saved enough…, she sent it to her husband…so he could join them…” But that was not to be. ‘Tell me again what he said,’ she asked. “During the voyage [to New York,] he heard so many derogatory things about the Mormons, and about the Indians killing people in the west, and he got frightened. When he arrived…he turned around and went back to Denmark.” More tears fell from her eyes. She never heard from her husband again. A few years later her child died of typhoid fever. Even so, she retained here kindness and faithfulness as a member of the church. She married again, had seven children and cared for several more. Her youngest child, Harvey, later said, “My mother was a wonderful person…she just couldn’t see anything bad about anyone…my parents never had anything…they gave it all away…we had a happy home…she just loved everybody and everybody loved her…”

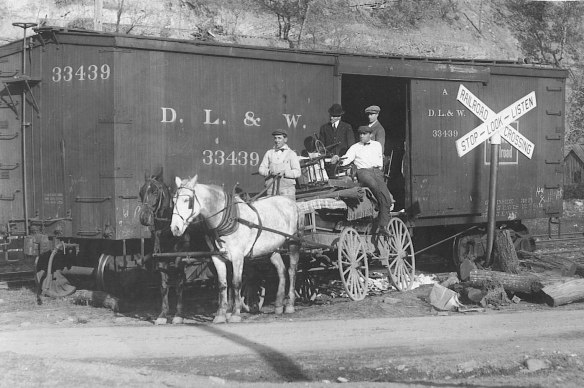

Anne Marie gasped as her knees buckled. She sat down immediately on the rough porch covering her mouth with one clinched hand, holding her chest with the other. She widened her beautiful gray eyes to prevent tears from falling, which eventually spilled to the ground. She had married in Denmark, leaving her “quaint Danish home…dirt floor and thatched roof,” and set sail with her new born child promising to work hard and send money so her husband could join them in America. Her mother and brother had immigrated earlier and by their toil had saved and sent enough for Anne Marie to come. “She crossed the North Sea,” where she and the child suffered terrible sea sickness. Now in Richfield, Utah, “she scrubbed floors and cleaned to…take care of her little son. When she had saved enough…, she sent it to her husband…so he could join them…” But that was not to be. ‘Tell me again what he said,’ she asked. “During the voyage [to New York,] he heard so many derogatory things about the Mormons, and about the Indians killing people in the west, and he got frightened. When he arrived…he turned around and went back to Denmark.” More tears fell from her eyes. She never heard from her husband again. A few years later her child died of typhoid fever. Even so, she retained here kindness and faithfulness as a member of the church. She married again, had seven children and cared for several more. Her youngest child, Harvey, later said, “My mother was a wonderful person…she just couldn’t see anything bad about anyone…my parents never had anything…they gave it all away…we had a happy home…she just loved everybody and everybody loved her…” Opportunity was slim in Newton Utah in 1899. Walter and Eliza Caroline journeyed by steam locomotive from Newton to Indian Valley Idaho, anxious for promising, “cheap and plentiful” land further north. A “lawless element…infested the railroad,” so, “mother and the two baby boys rode in a passenger car” while Walter guarded the family’s possessions in a box car. Aroused from the continuous clickety-clack, he heard galloping horses and rough voices outside the train. An instant later, rough fingers wrapped around the end of the box car door. “Get out o’ here,” he yelled. The door opened a few inches with a slow screech. The Griffin “livestock” stirred, “penned-off at one end,” of the car. Their furniture and [belongings] were at the other end, and their heavy “machinery, wagon and food…were…near the doorway.” No stranger to guns and outdoors, he had learned hunting and defense from his frontiersman father. Walter grabbed his Colt .45 from beside his books and lantern. He stood, shoulders back, chin high, and aimed. A “tough” face looked in. Walter pulled back the hammer; the click filled the car. He “tighten[ed] his finger on the trigger.” The intruder “read the message in his eyes,” muttered, then backed out and “dropped off” the train. The family made it safely to Indian Valley, prospered “handsomely” for ten years then returned to Utah due to concern over “raising their family in this relatively untamed country.” Moving from “a prosperous…ranch” in Idaho to a “alkali-infested lake shore [in Utah] brought years of toil and struggle. However, [Walter] tackled it resolutely, often stating that, ‘hard work and perseverance could overcome any obstacle.’” #AncestorClips

Opportunity was slim in Newton Utah in 1899. Walter and Eliza Caroline journeyed by steam locomotive from Newton to Indian Valley Idaho, anxious for promising, “cheap and plentiful” land further north. A “lawless element…infested the railroad,” so, “mother and the two baby boys rode in a passenger car” while Walter guarded the family’s possessions in a box car. Aroused from the continuous clickety-clack, he heard galloping horses and rough voices outside the train. An instant later, rough fingers wrapped around the end of the box car door. “Get out o’ here,” he yelled. The door opened a few inches with a slow screech. The Griffin “livestock” stirred, “penned-off at one end,” of the car. Their furniture and [belongings] were at the other end, and their heavy “machinery, wagon and food…were…near the doorway.” No stranger to guns and outdoors, he had learned hunting and defense from his frontiersman father. Walter grabbed his Colt .45 from beside his books and lantern. He stood, shoulders back, chin high, and aimed. A “tough” face looked in. Walter pulled back the hammer; the click filled the car. He “tighten[ed] his finger on the trigger.” The intruder “read the message in his eyes,” muttered, then backed out and “dropped off” the train. The family made it safely to Indian Valley, prospered “handsomely” for ten years then returned to Utah due to concern over “raising their family in this relatively untamed country.” Moving from “a prosperous…ranch” in Idaho to a “alkali-infested lake shore [in Utah] brought years of toil and struggle. However, [Walter] tackled it resolutely, often stating that, ‘hard work and perseverance could overcome any obstacle.’” #AncestorClips

It was Christmas of 1909 just before my dad was to come home [from his two-year mission.] We were down to board floors and paper curtains [having sold the furniture piece by piece.] We had large five-gallon lard cans to sit on; a stove, table, and a bed that we all slept in. We sat in bed and sang Christmas carols until…it was time to go to sleep. We only had a bowl of rice that night for our dinner… We went to sleep hoping…for Santa to come. I woke up to the sound of crying. I went into the other room and found Mama crying. I asked what the matter was. She said…she was so grateful and happy to her Heavenly Father, and told me to go back to bed so Santa could come. I…was wakened again by her sobs. I went to sleep the third time and woke up at 7:30 am with mother still crying. As we all came out of the bedroom she made us kneel in prayer before we could see our toys. I will never forget the prayer my mother offered, thanking the Lord for his goodness to us. We then went out on the porch; there was a doll and dishes for the girls, a tool box for the boys and a small decorated Christmas Tree and a basket of food… We danced around the tree and sang and went to bed that night with our hearts full of happiness and our stomachs full of good food. Brother Alma Winn was our Santa and he had eight children of his own… My mother had cried and prayed all that night. Her prayers were answered… How grateful I am for the faith of my mother and grateful…that we five little ones weren’t forgotten by a “Santa” who had been inspired to come and help us in time of need.

It was Christmas of 1909 just before my dad was to come home [from his two-year mission.] We were down to board floors and paper curtains [having sold the furniture piece by piece.] We had large five-gallon lard cans to sit on; a stove, table, and a bed that we all slept in. We sat in bed and sang Christmas carols until…it was time to go to sleep. We only had a bowl of rice that night for our dinner… We went to sleep hoping…for Santa to come. I woke up to the sound of crying. I went into the other room and found Mama crying. I asked what the matter was. She said…she was so grateful and happy to her Heavenly Father, and told me to go back to bed so Santa could come. I…was wakened again by her sobs. I went to sleep the third time and woke up at 7:30 am with mother still crying. As we all came out of the bedroom she made us kneel in prayer before we could see our toys. I will never forget the prayer my mother offered, thanking the Lord for his goodness to us. We then went out on the porch; there was a doll and dishes for the girls, a tool box for the boys and a small decorated Christmas Tree and a basket of food… We danced around the tree and sang and went to bed that night with our hearts full of happiness and our stomachs full of good food. Brother Alma Winn was our Santa and he had eight children of his own… My mother had cried and prayed all that night. Her prayers were answered… How grateful I am for the faith of my mother and grateful…that we five little ones weren’t forgotten by a “Santa” who had been inspired to come and help us in time of need. With all hopes of emigration from Norway to Zion, Ole’s father died leaving a widow and nine children. Fighting despair with faith, the whole family was gathered in the Rocky Mountains within six years. During his youth in Utah, Ole worked as a laborer, miner, hotel mechanic, then railroad foreman. In 1899, he married Halvorine Halvorsen, also of Norway. Nine years later, on a Saturday night, a knock came at their home. Ole excused himself from the dinner table, then returned and invited Halvorine to join the conversation with the Bishop. “All children listened at the door.” Ole had received a call to serve a mission in Norway. “After some discussion, Halvorine said, ‘Ole, accept this calling. I am sure the Lord will provide. If it hadn’t been for the missionaries, we wouldn’t be here today…’ Ole quit his job [and] mortgaged the home,” but funds were scarce. How could he go, an associate asked? Ole said, “The call has come to me… God will open up ways…” Ole fulfilled his mission, returned as a fine leader. In numerous church positions he enjoyed a “rich portion of the Holy Spirit of God.” He and his counselors “awakened and brought into activity many of the men who had become inactive.” As a mechanic, he could “fix anything.” Ole became Temple foreman, and chief engineer for church buildings in Salt Lake City. The Presiding Bishopric of the church said, “Ole was the ‘guardian angel’ of all the Church buildings…” “As you look at the Temple, as you go through the ins and outs of these buildings, you see [Ole’s] fingerprints everywhere…I glory in the steadfastness of this man…”

With all hopes of emigration from Norway to Zion, Ole’s father died leaving a widow and nine children. Fighting despair with faith, the whole family was gathered in the Rocky Mountains within six years. During his youth in Utah, Ole worked as a laborer, miner, hotel mechanic, then railroad foreman. In 1899, he married Halvorine Halvorsen, also of Norway. Nine years later, on a Saturday night, a knock came at their home. Ole excused himself from the dinner table, then returned and invited Halvorine to join the conversation with the Bishop. “All children listened at the door.” Ole had received a call to serve a mission in Norway. “After some discussion, Halvorine said, ‘Ole, accept this calling. I am sure the Lord will provide. If it hadn’t been for the missionaries, we wouldn’t be here today…’ Ole quit his job [and] mortgaged the home,” but funds were scarce. How could he go, an associate asked? Ole said, “The call has come to me… God will open up ways…” Ole fulfilled his mission, returned as a fine leader. In numerous church positions he enjoyed a “rich portion of the Holy Spirit of God.” He and his counselors “awakened and brought into activity many of the men who had become inactive.” As a mechanic, he could “fix anything.” Ole became Temple foreman, and chief engineer for church buildings in Salt Lake City. The Presiding Bishopric of the church said, “Ole was the ‘guardian angel’ of all the Church buildings…” “As you look at the Temple, as you go through the ins and outs of these buildings, you see [Ole’s] fingerprints everywhere…I glory in the steadfastness of this man…” “Hannah gave Andrew to understand that her husband had to be worthy to take her to the temple. So he set about preparing himself…” At last the happy day arrived. He borrowed a team and sleigh and they drove from St. John, Idaho to Logan, Utah. Living near their extended family, “they had good land, flowing wells, excellent horses and fat cattle.” On urgings from “a sharp real estate salesman,” the large group sold-out and went to Canada to start a ranch with their “100 head of cattle and 14 sheep camps.” It was the coldest winter on record and, “they lost most of the herd.” In the spring, with much sorrow and homesickness, Andrew and Hannah returned to Idaho to homestead 160 acres at “the head of the Big Malad River.” The high sagebrush indicated good soil but required “long, tiresome work” to clear the land. In the summer, they lived in a log cabin; in the winter they lived in St. John where their five children attended school. In later years, he broke his ankle and also had a stroke but remained cheerful. Hannah learned to drive when he no longer could. When grandchildren, Ferril and Rex, came to visit, Hannah drove them around town to show them off. Before his death, Andrew said, “It is my advice to all young people to read and learn all they can about this wonderful church we have and never turn down an opportunity to labor in this great work that we as Latter-day Saints have accepted.” Andrew died on his 80th birthday. Hannah said, “We had a happy married life. We never had a quarrel… I am thankful I had such a good man and such good children.”

“Hannah gave Andrew to understand that her husband had to be worthy to take her to the temple. So he set about preparing himself…” At last the happy day arrived. He borrowed a team and sleigh and they drove from St. John, Idaho to Logan, Utah. Living near their extended family, “they had good land, flowing wells, excellent horses and fat cattle.” On urgings from “a sharp real estate salesman,” the large group sold-out and went to Canada to start a ranch with their “100 head of cattle and 14 sheep camps.” It was the coldest winter on record and, “they lost most of the herd.” In the spring, with much sorrow and homesickness, Andrew and Hannah returned to Idaho to homestead 160 acres at “the head of the Big Malad River.” The high sagebrush indicated good soil but required “long, tiresome work” to clear the land. In the summer, they lived in a log cabin; in the winter they lived in St. John where their five children attended school. In later years, he broke his ankle and also had a stroke but remained cheerful. Hannah learned to drive when he no longer could. When grandchildren, Ferril and Rex, came to visit, Hannah drove them around town to show them off. Before his death, Andrew said, “It is my advice to all young people to read and learn all they can about this wonderful church we have and never turn down an opportunity to labor in this great work that we as Latter-day Saints have accepted.” Andrew died on his 80th birthday. Hannah said, “We had a happy married life. We never had a quarrel… I am thankful I had such a good man and such good children.”